.jpg)

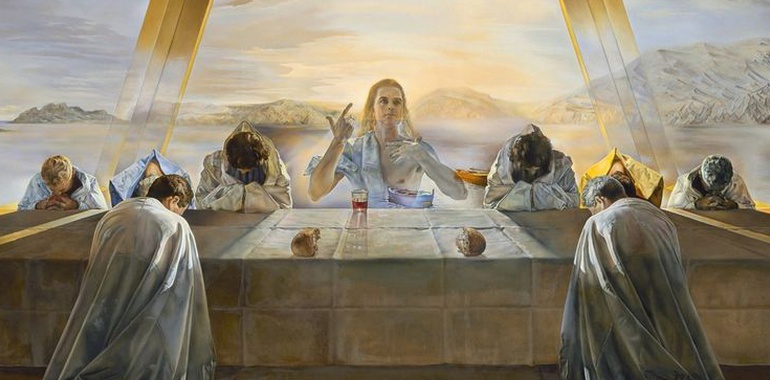

The Sacrament of the Last Supper/ 1955/ Salvador Dalí /oil on canvas/ National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Its Christian subject matter, simplicity of organization, and lack of shock value separate The Sacrament of the Last Supper from most of Salvador Dalí’s other works. Dalí’s reputation from the late 1920s to the mid-1940s was founded on his surrealist manner and use of Freudian dream imagery. This tableau of 1955 is both religious and realistic: the background accurately portrays the view from Dalí’s home on the Catalan coast of northeastern Spain. Although the rugged cliffs and eroded boulders of his native Catalonia had inspired many of the fantastic forms in his earlier works, here Dalí used the craggy bay of Port Lligat as a straightforward backdrop.

During the late 1940s, Dalí’s return to Christian imagery and traditional values was influenced by three factors: the devastating effects of the Spanish Civil War and World War II, his reawakened interest in classical art, and his reappraisal of Freud’s psychological principles after meeting the aging psychoanalyst in 1938. One classic derivation cited by Dalí in connection with his painting was Zurbarán, a seventeenth-century Spanish old master. The tousled hair of the praying figures, the kneeling postures, and the brilliant whites of their cloaks evoke Zurbarán’s precise, enamel-like handling of paint.

The Italian High Renaissance of the early 1500s was another major source for Dalí’s new classicism.

As in the harmonious presentation of Renaissance schemes, Dalí’s composition is clearly divided: foreground action and background scenery. The placement of men around the table is symmetrical, the same figure repeated in perfect mirror image on both sides of Christ. Moreover, the entire nine-foot-long picture is constructed according to complex mathematical ratios devised by Renaissance scientists and such ancient Greek philosophers as Pythagoras.

Dalí explained the reliance upon this elaborate geometric patterning just after completing nine months of work on the picture:

I wanted to materialize the maximum of luminous and Pythagorean instantaneousness based on the celestial communion of the number twelve: twelve hours of the day—twelve months of the year—the twelve pentagons of the dodecahedron—twelve signs of the zodiac around the sun—the twelve apostles around Christ.

Prepared and arranged by: Narges Saheb Ekhtiari