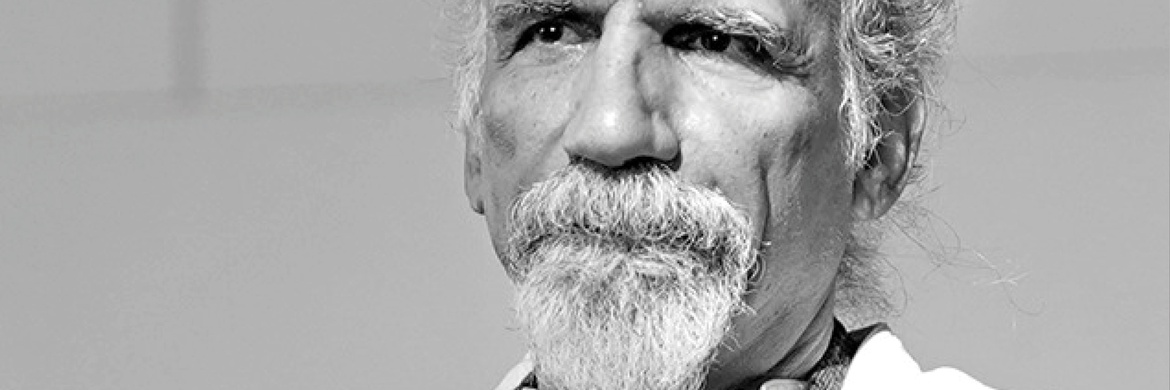

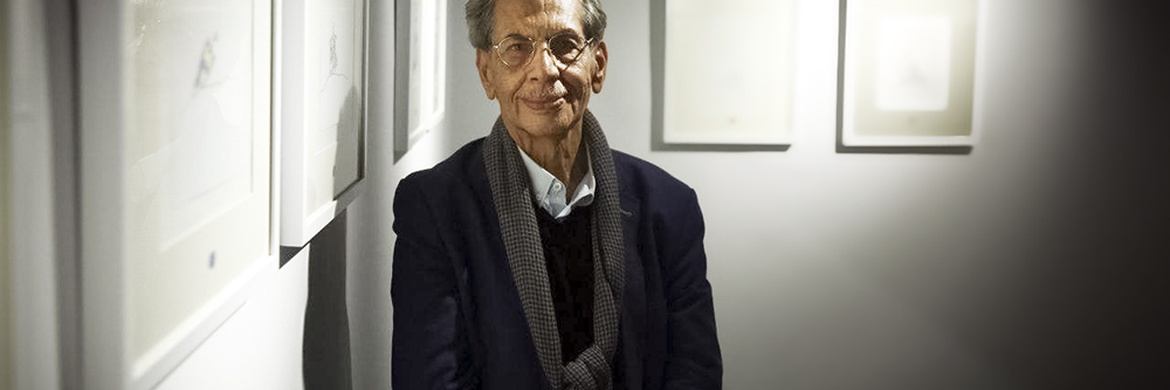

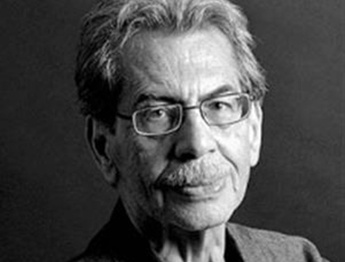

(This interview was conducted before his passing. Sadly, the great artist left us during the COVID-19 pandemic, leaving a remarkable legacy for Iranian and international caricature.)

Introduction

Almost everyone in the world of visual arts knows Master Kambiz Derambakhsh. His career and international achievements made him one of the most brilliant figures in introducing Iranian caricature to the world. He won first prizes in some of the most prestigious international cartoon competitions in Japan, Germany, Switzerland, Belgium, Turkey, Brazil, and Yugoslavia. In addition, he received many other international honors, and his works are preserved in renowned museums such as the Basel Cartoon Museum in Switzerland, Gabrovo Cartoon Museum in Bulgaria, Hiroshima Museum in Japan, the Anti-War Museum in Yugoslavia, the Istanbul Cartoon Museum in Turkey, the Warsaw Cartoon Museum in Poland, the Municipality of Frankfurt in Germany, and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Iran. He was born in Shiraz in 1942 and graduated from the School of Fine Arts in Tehran.

On the process of finding ideas

Q: How do you find ideas for your works?

I have no difficulty in finding ideas. I think I already have an archive of sketches and drafts that could last for the next twenty years, many of them still outside the country. New ideas are added every day. My real problem is time to execute them all. I hope I can realize as many subjects as possible, but I know that my lifetime will not be enough for the vast number of ideas I carry.

On execution time

Q: How long does it take you to complete a work?

My color works usually take about two half-days, from 8 a.m. to midnight. My black and white works generally take one full day, although it depends. Sometimes, the nature of the work allows me to finish up to 25 pieces in a single day. For example, I once had to design a calendar where each day of the year needed a drawing; on the first day, I completed 25 sketches.

On the nature of his works

Q: Tell us about your works.

Most of my current work is for advertising companies. I no longer work with newspapers, because I believe the tariffs for press cartoonists are a kind of insult. A janitor in an office earns as much in a month as a press cartoonist does. However, caricature truly comes to life only when it is published. In Iran, caricature is often reduced to politics, but political caricature is just a small branch. Like music, painting, or literature, caricature has many branches where artists can express themselves.

On advice to young cartoonists

Q: What advice do you have for young cartoonists?

It seems most of them are too absorbed in construction and technique, while the essence of humor is rather weak. When I had a solo exhibition in Gabrovo, the director later told me it was one of the best shows in the museum’s history. Visitors were surprised to discover such quality caricature from Iran. I see two great hopes for the future of world caricature: China and Iran. Iranian cartoonists have grown significantly after the revolution. Kayhan Caricature once played a key role in this development by generously sharing international addresses of festivals, something almost impossible to find under the previous regime.

My advice: work a lot. Don’t rush to publish collections. It took me twenty years to publish my first book (Without Words). Draw day and night, study the works of others, get to know the masters of the world. After that, publishing becomes essential, because caricature thrives only through being shared. Many artists create but keep their works hidden—it’s like staging a play in a locked room. An artist needs the audience’s reaction, even if it is negative.

On life choices

Q: If you were born again, would you choose the same path?

Yes. I would still try to realize as many ideas as possible. If I were given another chance, I would execute the ideas that I could not in this life.

On naming works

Q: Your works have interesting titles. Are they improvised?

That comes from professionalism. I’ve been doing it for years. Apart from being a designer and painter, I am also a humorist. I’ve played with words for years. Four of my books published by Ofoq Publishing are examples of my humor writing, such as Do Not Hurt the Ant that Carries a Seed or The Angel’s Diary. Wordplay and humorous writing are part of my craft.

On being a multi-disciplinary artist

Q: You are a multi-talented artist in different fields, but caricature is your main specialty?

Yes, but I’ve reached a point where my work transcends caricature. Caricature is mostly tied to the press, but my works have gone to museums, galleries, and private collections.

On the durability of caricature

Q: Some say caricature is less durable than other arts, more journalistic. Do you agree?

Like poetry or music, caricature has many levels. While newspapers were the main platform, since the 1950s caricature has found its way into museums and galleries in Europe. Restricting caricature to journalism makes it expire with daily events.

On distinguishing artistic caricature

Q: Where is the line between journalistic caricature and artistic caricature?

I went through the journalistic stage. To reach the next level, you must pass through that. When a caricature is visually and artistically strong, it naturally enters museums. Such works are less tied to everyday events like rising tomato or gas prices.

On museums acquiring works

Q: What criteria do museums consider in acquiring caricatures?

First, the artist’s line and style. Without a distinctive style, the work is wasted. My work, and that of others with a style, is recognizable even without a signature. Ideas also must be rare and unique. Repetition solves nothing.

On color

Q: Why do we see little color in your works?

Iranian press recently began printing in color, but often with poor quality. For me, color is used only when necessary. Eliminating color often brings purity. Someone once said: “You drew autumn, leaves are falling, so you don’t need to make them yellow; the viewer imagines autumn anyway.”

On recurring characters

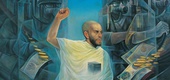

Q: We often see a recurring man in your works. Who is he?

Since about 1971, this figure has been present. He is a distilled human—without facial expression, yet through body language, you can feel his sadness, joy, or despair. He is international—if you put a Mexican hat on him, he becomes Mexican. He speaks a visual language with no captions, understandable worldwide.

On exhibitions

Q: Tell us about your exhibition in Paris.

I previously had a solo exhibition there where many works were sold. My book The World Is My Home was published in Paris, covering 35 years of my work with 18,000 copies. This time I brought a new book Visible Stories. I participated in two group shows: one at the Museum of Modern Art of Paris (highlighting the best works since 1960) and another in a gallery with nine large pieces, a fusion of painting and graphics.

On painting and digital tools

Yes, I studied Fine Arts and naturally began with painting. I work with both acrylic and oil, though I rarely paint nowadays. I never use computers—not because I refuse, but I don’t know how. In a way, I’m glad: handwork has a special value. Computers are like plastic, while handmade works are like wooden furniture—you feel the soul. Of course, computers are also tools; their value depends on how you use them.

On conveying meaning

Q: If in one sentence you could say what your ideas convey, what would it be?

They convey nothing predetermined. Each idea is a discovery. Many have good hands but lack ideas. People tell me I have both, and that they merge well.

On beginnings in caricature

Q: How did you start in caricature?

I must remember Mr. Tejaratchi, who worked in the magazine my father published. He was the first to make animation in Iran. He hand-painted film frames at home and projected them with a self-made projector. For me as a child, caricature meant Tejaratchi. Later, I discovered old foreign magazines in second-hand shops, where I found my first windows to world caricature.

First caricature

Q: What was your first caricature?

I drew two army sergeants, one with three “sevens” on his badge and the other with three “eights.” They argued about who outranked the other, although both were sergeants.

On definition of caricature

Q: How do you define caricature?

Caricature is a discovery. A cartoonist is constantly in search of unique discoveries. Critic Javad Mojabi once called me a “hunter of rare subjects.” Recently, I’ve explored subjects impossible to express in any other artistic language except caricature.